Goodnight, Adam. Goodnight, Eve. Goodnight, Functional Ontology. - Episode 128

Reviewing John Walton’s newest entry in the Lost World series: New Explorations in the Lost World of Genesis. With clarity and candor, Carey explores Walton’s theological evolution—particularly the move from “functional” to “ordered” creation—and discusses the role of biblical theology in understanding Genesis 1–3.

Carey also responds to popular-level criticisms of Walton’s work, emphasizing the need for good-faith engagement and theological humility. Along the way, she previews ideas from J. Harvey Walton’s dissertation and highlights the foundational theme of covenant, presence, and participation with God—over and above the traditional sin-salvation narrative.

What you'll hear in this episode:

- Why biblical theology matters and how it differs from systematic theology

- Walton’s shift from “functional” to “ordered” creation

- A defense against bizarre and shallow critiques

- The Eden debate: temple or divine space?

- Adam as priest—or not?

- A call for thoughtful, communal theological conversation

This episode is for anyone curious about origins, Genesis 1–3, and how to responsibly engage Scripture in its ancient context.

Blog post on biblical theology mentioned: What Is Biblical Theology?

Website: genesismarksthespot.com

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/GenesisMarkstheSpot

Music credit: "Marble Machine" by Wintergatan

Link to Wintergatan’s website: https://wintergatan.net/

Link to the original Marble Machine video by Wintergatan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvUU8joBb1Q&ab_channel=Wintergatan

00:00 - Good morning, John Walton.

03:25 - Reclaiming the Lost World: What’s Biblical Theology Anyway?

06:02 - From Functional to Ordered Creation

08:07 - Theology Isn’t a Solo Sport: On Thinking in Community

10:08 - What Is Biblical Theology, Really?

15:51 - Presence, Not Just Salvation: A New Canonical Meta-Narrative

19:51 - Walton, Heiser, and the Danger of Poisoned Wells

22:42 - Critics Gonna Critic: Footnotes, Family, and Exegesis

27:47 - Deploying the Old Testament: Not Redefining, Redeploying

32:24 - Presence, Covenant, and the Real Meta-Narrative

37:59 - Eden: Temple or Divine Space?

41:13 - Is Adam a Priest or Not?

44:13 - Covenant in Genesis 2–3: Is It There?

46:51 - Order Through Covenant, Not Civilization

49:06 - The Purpose of Covenant Isn’t Just Rules

52:28 - Ideas Have Weight: Why Theology Requires Method

54:56 - Redeploying the Sabbath: Practical Theology from Ancient Wisdom

56:43 - Should You Read This Book?

57:37 - What’s Next: Heiser, Divine Council, and More

59:20 - Sign-Off: Not About Finding the Lost Ark…

Carey Griffel: Welcome to Genesis Marks the Spot where we raid the ivory tower of a biblical theology without ransacking our faith. My name is Carey Griffel, and this week I thought I would take a little bit of a break from alcohol. No, not like that. And get into John Walton's new book. Do a little bit of a review and a response, share a few thoughts about it.

[00:00:34] And John Walton's new book led me then to read his son's dissertation. So this would be J Harvey Walton's dissertation. And that is got a whole lot of information that I would like to share and discuss, but it's a really big deal. So I'm going to talk about the dissertation another time, and this time I'm going to focus on John Walton's new book, but that does involve his son's dissertation's work.

[00:01:06] Now you can find his son's dissertation online, so you can go and find that and read it for yourself. It's very interesting ideas. I do not agree with a lot of it, but I do agree with a lot of it as well. So that's a lot of interesting stuff for the future.

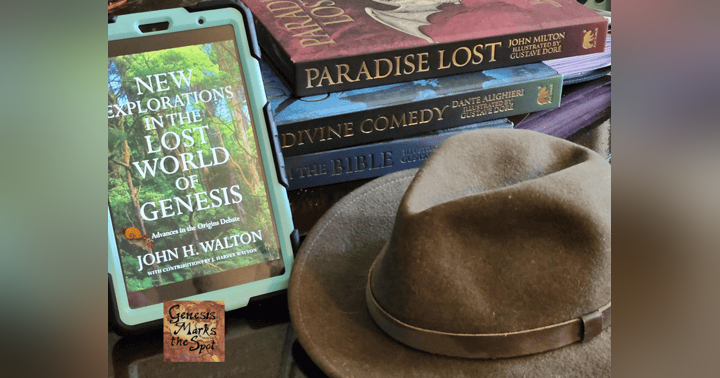

[00:01:25] But as I said, today we're gonna talk about John Walton's new book. New Explorations in the Lost World of Genesis, Advances in the Origins Debate. This is part of his Lost World Series, and I know some of you are familiar with John Walton's work and some of you are not. And if you're not familiar, I've been trying to decide whether or not this would be a good book to pick up for you or not. I halfway think it would be because this is a pretty broad overview of a lot of his ideas, plus the fact that much of this book is in the series of questions and answers, which I think is really helpful for his work because he has a lot of people who don't quite grasp what he's saying or people who misrepresent him. Or whatever. And so having this question and answer format is super helpful.

[00:02:25] But probably I would actually suggest that if you are brand new to John Walton's work that you go read The Lost World of Genesis One before you read this book. I think that is a really good introduction to what he's doing.

[00:02:42] Of course, a lot of people read that and they get a little bit freaked out in the way that he's talking about it, and that's why we have these questions and answers in this book. But nonetheless, I'll leave it up to you. It's a suggestion just to go read that book before you read this one though.

[00:03:00] But I would not say that you have to read all of his work in order to read this one. That definitely is not the case. You do want kind of a familiarity with what he's saying and how he's presenting it, and you know, you can also get that simply by going and watching some podcast interviews or YouTube interviews or whatever. He's got a lot of good content out there.

[00:03:25] Now some people get a little bit concerned because of the name of this series, right? The Lost World. That was his choice to name it that. But he's come to think that, well, yes, this is kind of what we're doing. We are reclaiming the lost world of the Bible. And really this is the purpose and intent of what biblical theology is meant to bring us.

[00:03:50] Some people are a little bit uncomfortable with that. A lot of people think, oh, well, you're reinventing things. You are suggesting that we've not understood the Bible all of this time. And that's where his Q and A answers in this book will come in very handy. He gives very good answers to those kinds of questions and really explains the purpose and intent and focus of such biblical study that doing.

[00:04:20] In fact, that might be one of my favorite parts of this book, is some of his explanations there, because that's a hard thing for a lot of people. A lot of people don't understand how biblical theology is approaching the Bible and how that doesn't have to be a threat to normal or systematic theology, although sometimes it does kind of knock against those things and say, well, is that really how we should be reading this? Because it's absolutely fair to ask what the intent of the biblical authors was.

[00:04:57] All right. I'll probably talk a little bit more about biblical theology in detail in a little bit here. But what he does in this new book is he describes his old way of thinking and the things that he's brought out before, and then he also describes some ways in which he's changed his mind. And that's not a bad thing. That's a very good thing. That's the sign of a really good critical thinker. Can you rethink the things that you're talking about in more helpful ways, in ways that describe it a little bit better and even change your mind on some things?

[00:05:36] That's a very positive thing here. Now, this isn't any kind of a total overhaul of his ideas. If anything, I would say it's more of a refinement and a better way of explaining the same ideas in a lot of places. He does have direct shifts and changes, but for a lot of this it is just about explaining it in a better way.

[00:06:02] So one of John Walton's big ideas is the idea of explaining Genesis one as a functional creation. He describes in great detail in much of his work how the person in the ancient Near East, this would be the Bible's earliest context, how they really didn't think in terms of material creation like we do today.

[00:06:29] And I know that that is a little bit of a scary idea. Like, whoa. Well, God is eternal, but matter can't be eternal. So what is all of this about? Well, frankly, we have to deal with the text as it is, not as we wish it was.

[00:06:47] And the fact is, people in the past thought differently than we do today. They had different concerns. They were understanding the world in a just a different way than we are. I don't know how many times I can say that the ancient person was simply thinking about the world with different concerns than we have. This isn't a threat to Christian theology at all.

[00:07:13] But at any rate, John Walton used to talk about a functional framework for creation. He has now shifted to talk about creation in the form of order, and he's found that to be actually more fundamental and really also easier to grasp as a concept. Because when you're talking about like function, you could be just doing something as simple as naming something, assigning a task to it. But what you're doing when you're doing that is you are creating order in your life.

[00:07:50] And so I have found his change from functional to ordered creation to be a really positive aspect of what he's talking about here in this book. And it's very crucial to what we're going to be getting into in some of the more major differences.

[00:08:07] Now, part of the reason and the ways that Walton has changed his thinking in this is because of interaction in scholarship with his son. I've seen some people bring this fact out and kind of act like it's a real problem. But really it's such a blessing to have people in your life who you can talk to about your ideas, who understand what you're saying and who can think things through with you. This is fundamentally why I don't think theology is a solo pursuit. You have to do it in community. In fact, you have to do pretty much any good thinking in community. And that's a positive thing.

[00:08:54] I know that it's very hard for a lot of people today who are in church and they are interested in deep, deep Bible study, but it doesn't seem like anyone else around them is interested in that, and that is a hard place to be.

[00:09:11] And I really sympathize with those of you who are in that kind of a situation. That is hard and it is difficult. Because you need to be able to talk about ideas within a community of other like-minded people who are also interested. And when I say like-minded, I don't mean that we're all gonna have the same ideas.

[00:09:34] That is literally the opposite of what I'm saying. You have to engage with people who are going to think differently from you if you're gonna have good thoughts at all. That's just the way good thinking happens. And Bible study should be partly about good thinking. Now of course we have the Spirit, we have all kinds of direction that the Spirit can give us in our study, but that shouldn't be an excuse to avoid or not care about studying in community.

[00:10:08] Now that kinda brings us to the topic of biblical theology, because biblical theology is a thing that is, well, it's a new kind of an idea. And I say new as in maybe like 150 years old, kind of new. And it's not that nobody before this time was doing anything like biblical theology, because that is not the case.

[00:10:34] But biblical theology as a particular methodology is a fairly new concept. So then the question is, well, if it's new and this is not the way that the Christian Church has always done theology, then what are we doing? Well, first of all, I want to say that there is no single way that the Christian Church has always done theology. We have, however, always done theology in community and in conversation with other people, and that's important.

[00:11:10] Now, I won't take a whole lot of time to define the methodology of biblical theology here because it's complicated and because it's going to depend on who's doing the theology. There are many types of biblical theology and they're not all the same, and that is a bit of a critique against it for some people because it's like, well, everybody can just make up their own method??

[00:11:36] I mean, kind of. That's what we've seen through church history. The early church fathers, they weren't doing theology like their predecessors, exactly.

[00:11:47] Sorry. That's just kind of the way things are in the realm of ideas. Plus the fact that you have different pastoral concerns in different places, and so when you're faced with different concerns, you're going to need to kind of think on your feet in order to address those concerns because the Bible doesn't lay out everything that we need to know for faith and life.

[00:12:14] So if you want to know more about biblical theology, you can go over to my blog where I talk a little bit about that and some of the methods, and in that blog post, there is a link to a book where you can read more about it. But basically at its most fundamental level, biblical theology is trying to understand the Bible in its own context. And there are many different contexts to the Bible. We have historical contexts, we have literary contexts, we have geographical contexts.

[00:12:50] And so biblical theology is generally as opposed to systematic theology. Systematic theology is what most of us are used to hearing about in church. The doctrine of sin, the doctrine of God, the doctrine of evil, the doctrine of salvation. And what systematic theology does is it pulls out a single answer to our questions from the entire Bible witness.

[00:13:19] But what systematic theology is not good at doing is recognizing that the Old Testament and the New Testament are entirely two different contexts. And even within the Old Testament and the New Testament, we have different contexts. The gospels are in one context, whereas the epistles are an entirely different context.

[00:13:43] And those things matter for how we can read those books. They matter for the points that the authors are making in those books. What is the purpose of the writing?

[00:13:54] So yes, biblical theology and people like John Walton do tend to challenge long held Christian assumptions, but it doesn't mean they're rejecting Christian theology. It's simply a fact. People at different times think differently, have different concerns, and have different purposes.

[00:14:17] And by the way, John Walton is not only stuck in biblical theology and trying to make biblical theology everything. Nor is he trying to pit the Old Testament versus the New Testament as if they have to disagree about something. I was watching an interview with John Walton on the YouTube channel, What Your Pastor Didn't Tell You, and what Walton said was that the New Testament authors deploy the Old Testament texts.

[00:14:49] So they're not trying to reinterpret the original context. They're trying to use it in their current time, and frankly, that's what we have to do too. So understanding how the New Testament authors can do that with the Old Testament books can really help our actual application and practical theology today.

[00:15:12] So even though biblical theology and systematic theology kind of seem at odds, they really ought to be married together in a solid theological approach. If you only have biblical theology, then you're not able to utilize theology to answer modern questions. That's a big problem.

[00:15:32] But biblical theology does have answers embedded within it, and if we understand the theological messaging of that theology, then we can extrapolate that in order to deploy it in our own times. That's necessary for the church.

[00:15:51] Now, one of the things that people might have a little bit of problem with is that Walton says that Genesis does not feed into a sin salvation narrative. That sounds a bit scary to a Christian because to us, we tend to think of everything wrapped up in sin and salvation. And we think, well, surely everybody in the Bible was also worried about sin and salvation.

[00:16:20] Some of us might get a little bit confused when we go back to our Bibles and read, and we have to shoehorn that meta-narrative into what is going on, and it doesn't seem to fit perfectly. What we need to do instead is read the text for what it's saying, and then we can extrapolate that out into what it means in that wider Christian perspective of sin and salvation.

[00:16:48] Because I'm not suggesting, and I don't think Walton is suggesting that we just drop that or jettison it, but it has to fit in with what the actual purposes of the biblical authors are saying. And Walton's argument rests on two things. The idea of God's presence and the idea of our relationship with him. And those are two things I talk about all the time. And they lead directly up to the incarnation. They lead to the Christian Church. They lead directly into how we should be living our lives and the focus we should have.

[00:17:29] There is a recent long track record in American Christianity, at least, American evangelical Christianity, that there is such an emphasis on the sin- salvation narrative that we miss the presence and relationship. And when you're going straight to that sin- salvation thing, then you are tempted, and many people do this, they go to the idea that it's all about our lives after we die. But really what we should be seeing is how this plays into our lives here and now. And that is also about eternal life. But what we're worried about right here and right now is how we live and how we relate to God. And how does that relationship that we have with God then flow out into the world around us?

[00:18:25] This is very much stuff that I talk about all the time. This is why I think the Bible starts at Genesis one and not Genesis three, which is kind of where the sin- salvation narrative basically starts. It's like, well, what's the point of the first two chapters?

[00:18:44] But I get it. I get that it's really tough to kind of push back on these traditional ideas. Although I will say that we tend to think that the way that we're thinking about things right now is the way the church has always thought about it. And that is simply not the case either.

[00:19:04] Now, I am not intending to try to do any kind of hit piece on anybody else out there who's doing the work of God. Okay, that is not my goal. My goal is not to poison any wells. My goal is not to try and discount or hit against the work of anybody else. So I'm not gonna name any names here, but I do think that ideas have traction. And so when you put an idea out, it now has a life of its own. And there is a responsibility to deal with those ideas when they are not accurate or when they're misrepresentations or when they just don't really fit into the conversation in a productive or helpful way.

[00:19:51] Now, part of my concern, honestly, if you know about Dr. Heiser and you're familiar with his work, and if you're familiar with John Walton and you're familiar with how those work together and how they don't, it's kind of a weird little section of theology right there.

[00:20:08] Dr. Heiser and Dr. Walton, I think agreed more than they disagreed, but they have some firm differences. And that's probably another topic for another time to really dig into those differences because they're interesting. And they're useful to look at. And I don't personally think we should pit the two against each other as if they are somehow diametrically opposed.

[00:20:33] But I'm afraid that some things out there, including things that Dr. Heiser has said, and including things that Dr. Walton has said, it's kind of poisoned the well for some people. Either poisoned the well against Dr. Heiser or poisoned the well against Dr. Walton, and I don't think that's necessary. I think that they are both critical thinkers who want everyone to be able to engage in these ideas for themselves.

[00:21:04] And that is their goal.

[00:21:06] And I think that's everyone's goal here. There's no reason to be afraid of an idea. You can reject an idea, that's fine. There's nothing wrong with rejecting an idea. I do it all the time. But a lot of times the ideas you're rejecting are coming along with ideas that you should actually be considering as well.

[00:21:28] So please don't let anything that I say poison the well against anyone else. I know I have my own opinions. Some of them are very strong. I know that I'm sometimes very straightforward and I try not to sugarcoat things because I feel like I'm talking to adults who should be able to understand what I'm saying and have good faith communication.

[00:21:53] Unfortunately, it is the case that not everyone has good faith communication with other people, but that's kind of not my problem. If somebody doesn't wanna have good faith communication with me and understand what I'm saying, well I can't force them to.

[00:22:10] So anyway, I'm just saying that because if you're in the realm of ideas and you're trying to get other people to see what you're seeing. You might be in that state as well of trying to communicate something to somebody who just doesn't want it communicated. And sometimes it's necessary to just disengage, but you know, when that happens, usually they have a really deep reason for it that might not have anything to do with the topic at hand.

[00:22:42] At any rate, like I said, ideas have traction, and so I wanted to respond to a few criticisms that I've seen lately. One of those criticisms that I actually mentioned before is that Walton's book has a lot of footnotes that just reference his son. Now, I don't know whether or not J Harvey Walton has his doctorate because I can't find any actual reference that he is Dr. Walton, so I don't know what his status is, but I do know that he has a PhD dissertation out there and this dissertation is high level scholarly work.

[00:23:26] So no, this isn't just Walton sitting on the porch with a cup of tea in his hand talking to his son and coming up with new ideas together. That is not anything near what is going on here. Walton has plenty of footnotes that are not his son. His son has plenty of footnotes that are not his own. Lots of high level stuff going on here. And it might take me a minute to unpack his dissertation so that you can even appreciate what his argument is and how he's making it.

[00:24:00] But I also wanna say it doesn't really matter if his son has scholarly citations or not, because although there is a very strong need for academics, scholarship, peer review literature, all of that is so important. But on the other hand, if you've got a good critical thinker who has researched some of this stuff and who understands a logic and just the ability to challenge a thought.

[00:24:31] Well, those are people that you want to engage with in discussing your work if you are any kind of an intellectual thinker. If you don't have people like that around you, you're just not gonna have very good work. You need people to challenge your thinking. So it really doesn't matter if his son has dissertation level work or not, because he seems to be a really good thinker with some new ideas.

[00:24:59] Another criticism of Walton's book is the suggestion that Walton is rejecting the New Testament use of the Old Testament.

[00:25:08] In fact, here is a quote that a critic has given in defense of this idea. This is from page 2 39 of Walton's book, and Walton says, quote, " The principle of Scripture interpreting Scripture does not give us permission to allow New Testament voices and perspective to dictate the exegetical conclusions of the Old Testament." End quote.

[00:25:37] The person giving the critique says, quote, " Again, Walton continues to claim that he's got the Bible figured out better than the Bible." End quote.

[00:25:48] Well, first of all, let's tackle that claim. Does Walton actually say that he has the Bible figured out better?

[00:25:57] Well, no, he doesn't say that. On page five of this book, at the beginning, Walton says, quote, " A refrain that I often repeat is that it is not my intention to present the right answer and to expect everyone to adopt my conclusions. Instead, my job is to be a faithful interpreter and to put information on the table that others may not have so that they can make more informed decisions." End quote.

[00:26:31] And as I've said, it is a really good idea to keep thinking and challenging your ideas as Walton has been doing.

[00:26:40] Walton says on page six, quote, " Beyond taking advantage of opportunities to communicate ideas, I have been trying to develop deeper understanding and new ideas through ongoing research and thinking." End quote.

[00:26:57] Frankly, I don't see a problem with that. I can kind of see how that might seem like a challenge to traditional Christian theology or whatever. But as intelligent human beings, we really are called to think and evaluate, and today we have so much more information than we used to have with linguistic studies, with archeological information, and we would be fools not to use those things in our studies with the Bible.

[00:27:30] Going back up to the quote that the critic used, the quote that seems to say that Walton's discounting the New Testament use of the Old Testament. Well, let's put it in the wider context of what Walton is saying on those pages.

[00:27:47] Walton says, quote, " Even when further revelation about a topic occurs, such as how to understand the resurrection, the afterlife, or the doctrine of the Trinity, that later revelation may help to formulate our theology, but it does not change what was going on in the minds of the earlier authors and audiences. Consequently, the principle of Scripture interpreting Scripture does not give us permission to allow New Testament voices and perspectives to dictate the exegetical conclusions of the Old Testament." End quote.

[00:28:28] As I say, this is just pure biblical theology. When Walton is talking about exegetical conclusions, what he is talking about is looking at the Old Testament in its context and understanding what those Old Testament authors were communicating and why. What was their purpose and intent and concern?

[00:28:53] And again, the New Testament authors deploy that information, but Walton is just saying that they are not trying to reinterpret it for the original audience.

[00:29:06] And again, if you are familiar with Dr. Heiser's work, this is what Dr. Heiser was doing as well.

[00:29:14] As Walton says, quote, " Some may use Revelation to draw a theological conclusion that the serpent in the garden should be identified with Satan, but that does not change the fact that there is no evidence to think that an Old Testament audience would have come to that conclusion. The same cautions should be in place when we discuss whether the divine use of plural pronouns in Genesis 1 26, 3 22 and 1117 refer to the Trinity. In like manner, the autonomy of Genesis regarding Adam and Eve must be retained. What Paul says has to do with the points Paul is making as he redeploys Genesis for his audience in the theological discourse in which he is engaged. That neither dictates nor changes how we understand the message in the context of Genesis." End quote.

[00:30:16] As our critiquer again brings out, another quote from Walton. Quote, " I am now convinced that we should not feel compelled to think that Jesus and Paul are doing the same things as Genesis. For example, if the New Testament can be shown to be interested in Adam and Eve as individuals, that would not mean that Genesis had the same interest. Some might claim that the concept of the unity of Scripture could be invoked to claim that Genesis and the New Testament ideas about Adam should be conflicted. But that cannot be maintained. As mentioned in chapter two, we do not have to see Scripture's voice being in unison." End quote.

[00:31:00] I mean, I can see how that seems like a challenge to Scripture's integrity and authority, but we have to understand Walton in his own context, just like we have to understand the Bible in its context.

[00:31:16] It sounds like this quote from Walton is somehow denying like a New Testament focused meta narrative. But if you understand and read more of John Walton's work, I don't see how you can come to that conclusion.

[00:31:33] John Walton literally talks about something that he calls Immanuel Theology. This whole idea is what I talk about all the time. Genesis one is about God creating us in order to dwell with us to be in relationship with us and that he has desired this from the beginning. And the incarnation of Jesus is the fullest expression of that.

[00:32:00] Now the quotes that we've been using have been at the end of the book. The conclusion of a book is a really good place to go for the conclusion of the authors.

[00:32:10] But another good place to look for that is at the end of the first chapter because the first chapter has laid out some of the thoughts. And the first chapter is also going to conclude with some things that you can expect to see in the book.

[00:32:24] So let me read this lengthy quote from Walton. This is his last paragraph at the end of chapter one. Walton says, quote, " As is evident from the above synopsis, I do not see Genesis as feeding a meta-narrative of sin and salvation, a view that has long been common in Christian thinking. The longstanding problem for theologians has been that it is difficult to demonstrate that the Israelite authors and audiences were aware of such a meta-narrative. Instead, I maintain that these opening chapters of Genesis, while not articulating a meta-narrative, use the rejection of ancient ideals of order to launch a different meta-narrative. One that centers on relationship and presence, particularly as it is reflected in the covenant. Interest in these issues is pervasive in the Old Testament, evident, for example, in the covenant expression that Yahweh will walk among them and be with them, that he will be their God and they will be his people. In Leviticus 26, 11 through 12 one Kings 8 57, Ezekiel 34, 30 and 37, 26 through 28. Even prior to the covenant, these factors are evident in Genesis 5 24 where Enoch walks with God, relationship and presence. This focus extends into the meta narrative of the New Testament, as well. See John one 14, Matthew 28 20, 2 Corinthians six 16 and Revelation 21, 3. The incarnation extends the presence of God and the death and resurrection of Jesus provide for relationship in a full way. Pentecost features the presence of God in his people as a seal of the relationship forged with them through Christ. New heaven and earth are characterized by God's presence and relationship with him. This can therefore be identified as a canonical meta-narrative. Though the New Testament did not launch it, it just gave it new expressions as God's plans and purposes unfolded in Jesus. Genesis one through three launched the core ideas, which were then developed in the context of Yahweh's Covenant with Israel. End quote.

[00:35:05] Well, there you have it. He talks about a canonical meta-narrative that begins with Genesis one through three, extends through the work of Jesus, into Revelation 21. I don't know what more you want, if you want John Walton to accept a canonical narrative.

[00:35:26] This just isn't the sin and salvation narrative. But that doesn't mean it has nothing to do with sin and salvation.

[00:35:37] Now, there is some interesting little bit of tidbits here regarding the idea of sin and Genesis one through three, as I will hopefully talk about in the future with J Harvey Walton's dissertation. Walton basically denies that there is sin involved in the eating of the tree. That's a difficult view to take, and that's why I have to spend an entire episode trying to unpack that for you. And I'm not doing it in order to convince you of it because I'm not convinced of it either, but we want to be able to see how solidly his argument is. The only way you can do that is really by understanding it well.

[00:36:19] Okay. So we'll do that in the future, but I will point out that John Walton in this book, the Elder John Walton, is not denying a sin element here in Genesis three because he still says that this is an act of self will against the deity.

[00:36:39] So just because this whole narrative is not focused on a sin and salvation narrative, doesn't mean sin doesn't fit into the story. And it certainly doesn't mean that salvation doesn't fit into the story because you can't have God's presence and relationship without the aspect of salvation because that is absolutely crucial to the entire Bible's narrative in the Old Testament, as well as the new.

[00:37:11] I mean, there is a reason that the Exodus is the focus point of the Old Testament. So, you can't say that there's nothing about salvation and sin here. Okay? Like that's just silly. But the point is that shifting the focus and the center from sin and salvation to one of presence and relationship allows us then to start in Genesis one rather than starting the story in Genesis three.

[00:37:43] This is a point I find essential.

[00:37:47] Now I do briefly want to get into a few of the differences and ideas he brings out in this book regarding Genesis one through three. So let's talk about a couple of those for a moment.

[00:37:59] One of these ideas is that Walton has adjusted his thinking from Eden as a temple to Eden being divine space. Now, what's the difference there, you might ask, because a temple is divine space, is it not? Well, it is, but a temple is a divine space on earth that people build and that the divine will come and enter into it.

[00:38:29] The argument for Eden as a divine space rather than a temple... well, there's a few points here. One of them is that people don't build it. I mean, fair enough. Of course, God could build it and it could still be a temple.

[00:38:45] Another bit of evidence is that divine rivers flow from it. And that is like a source of the divine. So it's literally coming from the divine.

[00:38:55] J Harvey Walton's idea of this not being a temple is really particular to his arguments. And I don't really wanna tackle that here today, but he has a very particular reason why he's saying that the garden is not a temple because, well, in short, people aren't meant to be and live in the divine realm. And this was a common theme in the ancient Near East, right? Like people going into the divine realm was not only, not normal, but they really weren't comfortable there. It was not ordered like a human space.

[00:39:35] Now, regarding Eden as divine space versus temple, I don't see that as a big deal either way, personally. I am okay with the idea that it's a divine space. I actually kind of appreciate the distinction between divine space and temple, because like the Holy of Holies is meant to be the divine space in the temple, and that's a reflection of the heavenly divine space. So there's gotta be a heavenly divine space. And I don't really see a problem with the Garden of Eden being that. So this is kind of one of those points where I'm like, yeah, that's a good point. But it's really kind of such a nuanced point that it might not matter very much.

[00:40:21] Now, a second point that's related to that is that John Walton used to talk about Adam as a priest. In fact, he was one of the ones who convinced me of this typology, and he has now retracted that. And that is in relation to Eden being a divine space and not a temple. But also just a lack of explicit detail about Adam as a priest, which I'm like, well, that's fair enough, because that's kind of been my problem with it in the past. It's not really like this major theme that hits you over the head.

[00:41:00] My view is still that Adam is a priest and that he is an image that is in the temple. So for me it's like these ideas are possibly useful, but they're also overly nit picky.

[00:41:13] And here's what I think really. You have Genesis one through 11, which is primeval history. This is like way, way back in the day for the people, right? And these are stories that kind of set up and organize their world as Walton is arguing. And as such, because they're at the beginning, I don't think we need to presume that we're going to see all of the later elements in ideas like sacred space and the priesthood. We're not gonna see those things because those did develop in time for the people, and these are foreshadowings or typologies of it.

[00:41:57] So taking away the idea of temple or priest, you can kind of nuance that in a good way, but it's also not all that helpful if you make that firm distinction and say, well, that's not sacred space and Adam isn't a priest.

[00:42:14] Well, let's look at a different example, for instance, that I think might be easier to see. What about Noah's Ark? Is Noah's Ark sacred space? Is it a temple?

[00:42:26] My view is that it is the first human built sacred space, which parallels it with the temple. And we have the word atonement in there, which we'll have to talk about another time. But these descriptions and these words are used in order to point us in the direction of these later ideas.

[00:42:48] It does not mean they have to be the exact same as the later ideas. So the Garden of Eden can be divine space. It can also function as a temple. It is ordered as one, basically. Adam is not a high priest in the line of the Levites. Quite obviously. That doesn't make him not a priest.

[00:43:12] So you have like Noah's Ark, which functions as kind of this in-between picture of sacred, divine space, between the garden and the temple. These are all continuous ideas and just saying that it can't be the temple and Adam can't be a priest, that feels like way too far of splitting hairs for me. Because you're removing the ability to see the themes and parallels that are there. Things like Adam and Eve being dressed, Adam and Eve hearing and seeing. Those are things that both a priest would do, but also the temple idol will do. So we really have to be careful not to say this is either this or that, and that's the end of the story. When the imagery and the words are used and the whole concept is there, well, there you go. I, I don't know what else to say.

[00:44:13] One of the things that J Harvey Walton brings out heavily in his dissertation, or at least it hit me heavily, is the idea that he doesn't think there are covenant themes in Genesis two to three. Now again, he's got a whole argument for this and it's very interesting. We'll just have to talk about that later, sorry.

[00:44:37] But again, it's the same thing as with sacred space and priesthood. All of the elements for covenant don't have to be there in order for it to be a covenant or in order for it to be pre shadowing a covenant or to be in the typology of a covenant. Well that's how Typology works.

[00:44:57] So anyway, like I said, you can go and read J Harvey Walton's dissertation online. If you wanna go and do that so that you're prepared for my conversation about it, well, more power to you. It's not like it's that long. It's about the length of a book, but it is pretty heavy reading if you're not used to dissertation reading. And it might kind of drive you crazy for a few reasons too. Not gonna lie.

[00:45:25] But one of the really neat aspects that I think J Harvey Walton brought out that he helped his dad, John Walton, see, is this idea that Genesis one through 11 and the creation narrative and all of it is really focused on finding order in covenant. Now that doesn't mean we have to go full on into like Protestant covenant theology.

[00:45:54] We have to understand it from the perspective of the biblical authors, not the perspective of later systematic theologians or whatever.

[00:46:06] So lots of fun to look forward to. And I really think this is a neat idea and it helps explain how Genesis three is not just the fall that started at all, but it's actually part of the whole narrative, especially from Genesis two to 11 that is basically a polemic or a subversive attempt against ancient Near Eastern common knowledge and wisdom that human order is found in things like agriculture or civilization or kingship or legacy, or any of these other ancient ideas where people really found their meaning and order in life.

[00:46:51] But rather, the Bible is saying, you know, all of those things aren't bad by themselves. Wisdom and legacy and agriculture and community and kingship, all of these things are good in and of themselves. But they are not the ultimate good and the source of order for life.

[00:47:15] And this is a unique thing for the Bible. You go into other ancient Near Eastern literature and ideas and they do formulate these other aspects as the organizing principle for humanity, the organizing principle that the gods have handed down to humanity. Here you guys go, this is how you live an ordered existence. And it's things like the agriculture or the city or the king or whatever, and the Bible is pushing against that story and saying, huh-uh, that is not how we find ultimate order. The only way that's gonna happen well is through covenant.

[00:47:59] And the more this is going through my own head, I'm reading through Genesis or the Torah and I'm seeing aspects of how this theme is absolutely being brought out in those places as well. It's like, look, humans are supposed to participate with God in providing order on Earth. The problem is we tend to do that in our own ways and like, okay, well let's do this then, and it's not participating in God's view of things and God's order.

[00:48:35] It's like, yes, God, we have a relationship with you. We'll see you later after we get all of this worked out. But that's not what God wants for us. He wants true and legitimate participation where it is a both and kind of a thing, where it is God's order and relationship that is providing the means for us to create order in our lives. But that doesn't negate the actual work that we do.

[00:49:06] Again, it's participation, it's presence with God. It's that relationship. That's why we are the image of God. That's why we have the metaphor of the temple. That's why we have the rituals and sacraments that we have. This is why God came into humanity. To be with us. And it wasn't just to avert the sin of the fall. It's a much broader picture, and it's not just to get us off the hook of our sin. I mean, that can be related, but that is not the complete picture because really God wants us to have ordered existence here and he wants to live that with us.

[00:49:53] You know, it's interesting because I think back on my own theological and biblical education, through time trying to understand the imagery of the Bible. And I remember distinct times in either like a Sunday school class or something where the question of what is a covenant comes up.

[00:50:15] And early on in my biblical studies and theological life, even with a really good teacher who knew quite a bit about the Bible, we always came back to the explanation of covenant as a contract. Like it's a legal thing. And you know, I'm not saying that covenant isn't some sort of legal agreement or contract because that's part of its metaphor.

[00:50:44] But when we're focused on that as covenant, the tendency does seem to be, to kind of drift over into the rules section of things, right? Like, oh, to be in covenant with God means that we've got rules to follow. And again, it's not like God doesn't have things for us to do that we might define as rules.

[00:51:10] Okay, sure. That might be part of it. But is that the purpose? Is that why we have a covenant? God's like, well, here's my set of rules and if you break them, you are in trouble.

[00:51:25] Is that the picture of God that we get in Scripture? Well, it is kind of the picture we get when we look at Genesis three as if it's this breaking of rules that got them kicked out of the garden. I do think absolutely there is a better way of seeing that, and I'm excited to talk about that with Walton's dissertation because he has some very interesting trajectories there.

[00:51:53] Like I said, not gonna agree with it all, and that's fine. It's part of a conversation. And that's why we need continued academic studies because those tend to be the places where people can bring out ideas and they can have them bashed by other people. Better ideas come out after that, and that's kind of the point. But a lot of lay people have a hard time with that. Like if an idea is challenged, it's like challenging their identity instead of just challenging their idea.

[00:52:28] But anyway, you guys know that I talk a lot about that kind of thing and try to get us to understand that ideas are kinds of things that should be not attached to us. And they have their own life.

[00:52:46] And so when you put out an idea, it really is quite important that you realize that there's a seriousness to that. Regarding scholarship, you might think that it's just a free for all and you just toss all of the ideas out and see what sticks. I do think we have a responsibility to be more careful than that, which is why you need to ground what you're saying in not only good evidence, but good hermeneutics, good methodology.

[00:53:18] So you have things like biblical theology that can really dive into the context as opposed to just imposing something else onto the context that isn't there to begin with. And like what John Walton said, I don't think what Jesus was doing was reinterpreting Genesis or trying to impose a new idea on it.

[00:53:45] That doesn't mean that what he was saying is exactly the same thing, though. That's where we can get kind of a disunity. Not that it's really a disunity in the sense that there's not a continuation of the idea, but this was a common thing at the time. And if we're honest, it's common today to disconnect Scripture from its context and remove those moorings and use it for our own purposes.

[00:54:14] And you know what? Sometimes that's not necessarily bad because we have to move into the realm of application and practicality. So it's a hard task. I would never suggest we remove the moorings of the meaning of the text and the biblical authors. But like John Walton says, we do need to redeploy those ideas. And the redeployment might not be exactly what the original said. It ought to be faithful to it and it ought to continue this idea though, that is overarching Scripture where we have participation and relationship.

[00:54:56] There's a lot more that I could say about this book and what Dr. Walton brings out of it. And it's also funny to see these critiques and see the suggestion that he is somehow divorcing Christian theology because like in places for instance, he'll talk about the Sabbath. And he'll talk about the meaning and intent of the Sabbath in the original context, which again is presence and relationship, and it has hints of kingship and rulership as well.

[00:55:30] And then John Walton asked the question to himself, which I'm sure he's been asked this by other people of like, what do we then do if we want to be faithful Christians who want to take this concept of the Sabbath and incorporate it into our lives? And he actually gives practical ways you can do that.

[00:55:53] Ways that are rooted in the deep meaning of scripture and that help us incorporate that deep meaning of scripture into our lived worship lives. Like that's the whole point of what we should be doing here. It seems like that is Walton's deep heart to bring all of that out for us. And yeah, he might not do it in ways that we always agree with and that's fine. If we agreed with someone 100% of the time, we ought to be a little bit concerned about that.

[00:56:29] So at any rate, if you are curious about what Dr. Walton is saying in his books, you haven't had a chance to read any of them, this one isn't a bad one to pick up, to get kind of a full picture of what he's saying.

[00:56:43] If you have read some of his work and you've thought, well, he's wrong about this and this, and I wonder if he's changed his mind, this is a good book for that as well. If you've heard a lot about him and you're not really sure what to think because you don't know how accurate what you've heard is, this is an excellent book to pick up for that because I love how he's done the q and A sessions in his book and really answering questions that I know he's gotten dozens if not hundreds of times.

[00:57:17] So if you're interested in biblical theology, in temple cosmology, in the image of God, in the idea of covenant and presence, please go pick up a copy and see what he has to say and let me know what you disagree with in Walton's work, or his approach or whatever.

[00:57:37] ' cause I love to hear those things. And I've got my own list of things. Maybe in the future we'll do a whole divine council worldview comparison with Walton and Heiser, kind of bring out those differences and those similarities, because I think there's interesting things there, and I think that some of what Walton is doing is really, really helpful to our views in general, especially as it relates to like the reality of Adam, the reality of the gods of the nations, and all of that kind of thing. That seems like that should be a whole episode right there. But I will warn you that is going to be maybe a complicated question. And I'm excited to go through this dissertation and if you guys read it or read part of it and can send me some questions about it, that would be amazing. I'd love to kind of engage with more than just my thoughts here.

[00:58:42] Remember to go check out my blog for a description of biblical theology. And please, just because somebody says something or has an idea that you disagree with or that you don't like, that's no reason to poison the well against them or to say that you're not a fan of them or, well, whatever, there's no need for that. This isn't a popularity contest. This is the word of God that we're talking about, and hopefully we're working in it in the body of Christ. And that means that we have the same goals.

[00:59:20] At any rate, I will wrap this up here. And remember, this isn't about finding the lost Ark. It's about understanding the world that it came from.

[00:59:32] I hope you guys enjoyed listening to this episode. If you have any questions or you want to engage with me in some way, you can find me on my website at genesis marks the spot.com, where I do have some new merchandise on my store tab, or you can find me on Facebook. Really appreciate all of you who listen and who share these episodes with other people. That's very, very helpful to me and I hope to other people.

[01:00:04] And a big shout out to those of you who do support me financially. Thank you guys so much for what you do. really, really appreciate it. But at any rate, I wish you all a blessed week and we will see you later.